History of Communication Design– 18th to 20th century

/ Major Studies /

Lecture by Tomaso Carnetto

From the Middle Ages until today

We propose the following definition: Since its inception in the Age of Enlightenment, the role of communication design has been to shape the discourses and reality of a community according to the prevailing idea of what is right or wrong, good or bad, and to provide the physical or media objects that ensure that the expectations of what is good and right will be realized in the future.

We have five - sometimes very different - perspectives on what it means to become and be a designer for the 21st century. Each perspective is given by the task within each period for what we now call communication design. In other words, we take the perspective of the time (or, more precisely, what we think the perspective must have been, since design is always about expectations for the future) and apply it to our tasks today. The fact that a different task is given in each century (the division is used for ease of understanding) makes it clear that the results of design have in some sense failed in terms of the formulated expectations and thus had to be redefined. Taking into account the disappointed expectations of the last three centuries, we have to ask today what kind of expectations we have to fulfill now. In other words, we have to consider whether the task of fulfilling expectations is even possible.

Before the 18th Century

From an art historical perspective, we can say that before the 18th century, communication design was an obvious part of the arts. If we go back further (in a sense, before Giotto), we will see that what we now call art was an instruction on how to behave, claiming to be objective, in order to ensure the good pleasure of the gods or the one God (which means that it was given by the divine powers themselves). Only with the emergence of the artist as an individual does art become more than an official, God-given instruction.

18th Century

The birth of Communication Design with the “Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts”, the first general Encyclopedia, published in France between 1751 and 1772. Regarding the task, we can say that it is about what we now call Information Design.

19th Century

How the values of the bourgeoisie conquered Europe and the rest of the Western world, using the new mass media of printing, especially magazines (in the form of newspapers and hardcover books). The main task of this period was to initiate and regulate the social behavior, aesthetic preferences, and education of the so-called middle class.

20th Century

The promise of prosperity and a better world for all through consumption was, with increasing intensity (peaking in the 1980s), the main task of design in the last century. To this end, designers developed consumer products for which advertising became the most important communication tool.

21st Century

We need to discuss whether design and the communication content it provides should be based on the tripartite task of Information Design, Thematic Magazines (content and design for print, social media and digital publication) and Consumer Products (including advertising, package design, shop design, etc.), or if the profession is called upon to develop new types of objects or products to be designed, which we propose to call Participation Objects.

before the 18th Century

1st Unit

“Marginalia - the authors' space”

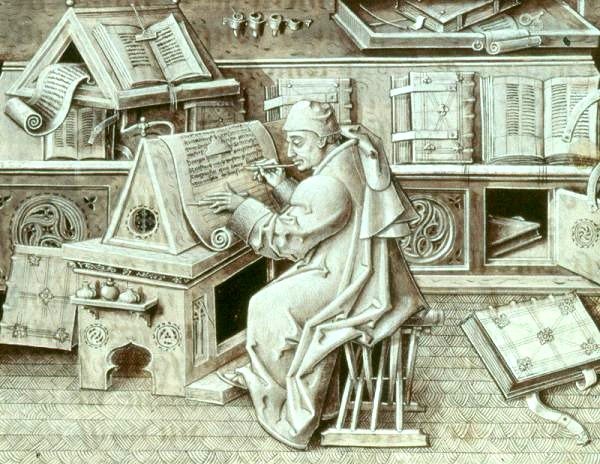

What we now call an agency or design studio was known since late antiquity as a scriptorium. Scriptorium, literally "a place for writing," is commonly used to refer to a room in medieval European monasteries dedicated to the writing, copying, and illuminating of manuscripts, usually by monastic scribes. The term is overused; few monasteries had dedicated rooms for scribes. They often worked in the monastery library or in their own rooms, much as a freelance artist works today.

An illuminated manuscript is decorated with embellishments such as borders and miniature illustrations. Commonly used in the Roman Catholic Church for prayers, liturgical services, and psalms, the practice became widespread for secular texts and books from the 13th century onward.

The earliest surviving illuminated manuscripts are from the Ostrogothic and Eastern Roman Empires and date from between 400 and 600 A.D. Examples include the Codex Argenteus and the Rossano Gospels, both from the 6th century. Most surviving manuscripts date from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, with a very limited number surviving from Late Antiquity.

Most medieval manuscripts, whether illuminated or not, were written on parchment, later on paper, and then bound into books called codices (singular: codex). A few illuminated fragments also survive on papyrus. Books ranged in size from those smaller than a modern paperback book, such as the Pocket Gospel, to very large books, such as choir books for choirs to sing from, and "Atlantic" Bibles that had to be carried by more than one person.

Paper manuscripts appeared in the late Middle Ages. The text had to leave space for rubrics, miniature illustrations, and illuminated initials.

The introduction of printing quickly led to the decline of book illumination. By the early 16th century, illuminated manuscripts were still being produced, but in much smaller numbers and mostly for very wealthy individuals.

Codices are among the most widely used objects of the Middle Ages, and thousands of them have survived. They are also the best-preserved examples of medieval painting.

In a sense, the first designers (long before design was invented) were monks. The general theme they worked on was how to become as pious as possible. The ultimate status of being pious is to become saintly, which means to be canonized by the authorities of the Catholic Church. The same was true of secular texts. In these cases, the question of how to become as pious as possible was related to the recognizability of this status, which turned out to be a question of social position, in other words, the degree of success and wealth denoted the degree of piety.

The work of writing, copying and illuminating a codex was thus a task that gave the scribe the opportunity to develop his individual status, both in terms of being qualified to enter paradise and in terms of climbing the social ladder in the earthly "vale of tears".

The fact that the scribe was involved in a very direct sense drove him not only to copy, but also - if he was allowed to do so (which again depended on his position, i.e. his success as a scribe) - to comment.

Although the placement and execution of each element was precisely prescribed in the codices, there was some space for individual additions, the margins (called marginalia), which allowed the scribes to add their own notes. Here we have the beginnings of individual authorship, albeit in a limited sense in that the additions were more descriptive of general ideas of What and Why, rather than personal impressions and experiences.

Generally, marginalia are markings in the margins of a book or other document. They can be scribbles, comments, glosses (notes), criticisms, doodles, or illuminations.

As mentioned earlier, before the invention of printing, books in Europe were copied by hand, first on parchment and later on paper. Paper was expensive, and parchment even more so. A single book cost as much as a house or today's luxury car. Books were therefore long-term investments, to be passed on to future generations. As a result, scribes and readers often wrote notes in the margins of books to aid later readers' understanding.

Manuscript annotations are found in most surviving books by the end of the 1500s. Marginalia did not become uncommon until the 1800s.

Of the 52 surviving manuscript copies of Lucretius' “De rerum natura” available to scholars, all but three contain marginal notes.

Additional Material

The Making Of Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts by Dr Sally Dormer

Image Glossary for Media Art (examples)

This is your task for Unit 1:

Watch The Making of Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts for a general overview of codex design.

Download the English or German version of "De rerum natura" (On the Nature of Things) / (über die Natur der Dinge) and start reading it.

Choose the chapter (for example “some vital functions”, book IV) that interests you the most. Mark the passages that are important for you.

Explain in short notes why the chosen passages are important for you.

Research the grids used in codices (see examples above). Use the measurements (often derived from the golden ration) to create a grid in InDesign or another layout program. You can find inspiration on how to do this here: Image Glossary for Media Art / Die Seitengestaltung im Mittelalter

2nd Unit

“Driven by Lust and Fear”

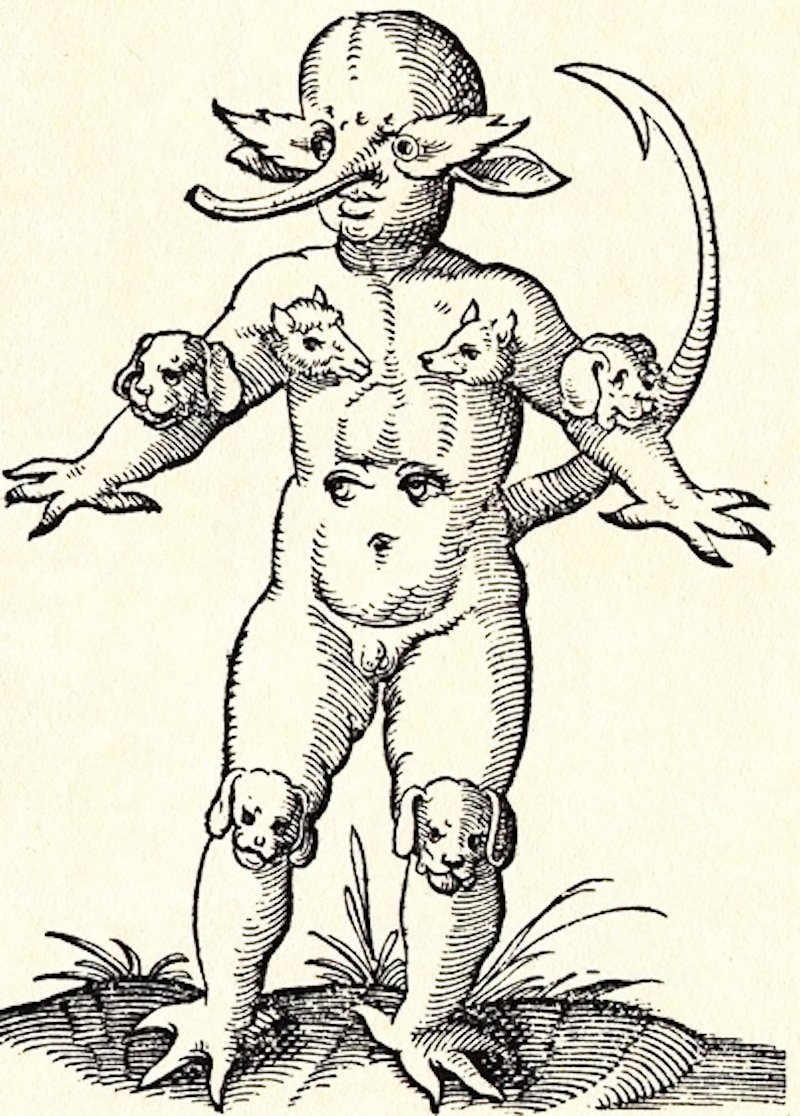

Curators of the exhibition "Medieval Monsters: Terrors, Aliens, Wonders", discussed the ways that medieval artists and writers demonized cultural outsiders, transforming religious and racial others into monsters, framing poverty and impairment as sin, and characterizing women as inherently deviant and dangerous. Focusing on medieval manuscripts illuminates the ways that these pernicious strategies are still in use today.

With "Terrors, Aliens, Wonders" we enter a very strange field, which we have to consider as a subject that still has a great influence on many people. In the time before the Enlightenment, it was a kind of omnipotent force, more powerful in everyday life than belief in God and the saints. What today is to be found in unsorted rests was once a complex system taken from the heathen world and integrated as good as possible into the Christian faith.

According to the thesis that communication design is beholden to the ideologies of its time, the task of medieval art (what we would now call communication design) was to communicate parts of this system as appropriate to a pious life and to condemn other parts as the work of the devil. In this way, the entire pagan system was embraced in the Christian duality of heaven and hell.

We can say that the work on an illuminated manuscript is in principle related to the meta-theme of Christian duality.

In addition to texts for prayers, liturgical services, and psalms, the subtopics unfold the various conclusions that can be drawn in terms of advice for a particular pious life, questions of jurisprudence for ecclesiastical or secular rulers, and, not least, the question of how to integrate the knowledge of natural science as it was handed down from antiquity in the oldest manuscripts, which were copied repeatedly.

With the idea that truth reaches people in the form of copied texts, as long as those responsible for copying are under the supervision of Holy Mother Church, the depiction of the monsters was a truth about the evil that will be encountered by those who have strayed from the right path.

This is where another source of truth comes into play, the inner vision of the copyist. Orthodox Christianity as well as Islam teaches that we are all subject to the temptation of evil. Only unconditional adherence to the commandments promises salvation.

Because the rupture between good and evil is thought to run through every human being, that is, driven by the lust to do something inappropriate to the good and the fear that doing so might cause infinite damnation, lust and fear produce their own visions.

We see that the depiction of good, as well as the depiction of evil, is based on two sources: on the one hand, the models of painting, sculpture, and manuscripts, and on the other hand, the inner visions. In a sense, authorship begins at this point, when the desire and fear that one feels is depicted in an individual way.

For the monk (or any other writer and illustrator) who is entrusted with the task of depicting the truth of what is good and what is evil, this is not only a task to be fulfilled as a given job, but a message to himself. What he produces affects him directly, his own fears, his own desires. This is the way the copyist becomes an author.

Even what we can call an inner vision is based on the inseparable interaction of emotions and visual images that come from outside. Authorship means to be aware of these impacts, to identify their multiplicity, to deconstruct the visions (from a slightly different perspective one can also call it inspiration) and to reconstruct them into something of one's own, both according to individually developed methodical procedures.

Instead, the copyist will use the inner vision only as an impetus to copy the source of whatever has had an impact on him or her. The copyist will do it with the attempt to get as close to the original as possible. This is the satisfaction of the copyist, to be told that his work looks exactly like this or that.

This is your task for Unit 2:

Activate your "inner vision”: Think about what you are afraid of and what affects your bodily desires, and find images for them just by working with pen and paper. Create corresponding figures (not a whole scenery!) and associate them with a short written description of your fears and desires. Work with your hand only.

Research the sources of your "inner vision". Collect the corresponding images from all the media you use and relate them to your figurations.

Deconstruct the media images and reconstruct them in your own way. Be guided by your initial sketches. Realize the figurations only as such, only as figures on blank pages. In reconstructing (i.e. creating) new figurations of fear and desire, make sure that you are working as an author and not as a copyist.

Relate your elaborations to the chapter of "De rerum natura" that you have chosen to work on. Combine the figurations, the chosen text and your notes within the grid, i.e. the editorial design you did according to the task of Unit 1.

Explain the relationship between the texts (the selected one and your own) and the new figurations that have been added. In fact, the relationship may be arbitrary at first glance, it may not seem to make sense. So start thinking about what the relationship could be (and believe me, there is one!) and write it down. This is where your intellectual authorship begins.

3rd Unit

“The Concept of Pneuma”

The opposite of the angels are the devil and the monsters. The former will lift us up to heaven, the latter will cast us down to hell. Both are created from pneuma, which is the pure sound and movement of the Creator's voice, the Holy Spirit.

The angels were created by giving an untouchable body to the pure movement, the devils and monsters (once also divine beings) lost the living breath by blaspheming the Holy Spirit.

The medieval understanding of the spheres

This diagram shows the medieval understanding of the spheres of the cosmos, derived from Aristotle. It was believed that at least the outermost sphere (labeled "Primũ Mobile") had its own intellect, intelligence, or nous, a cosmic equivalent of the human mind. Everything in the comos, down to the organs of the human body, was connected by pneuma.

To give a better understanding of what is meant by pneuma, we take the liberty of relating the Greek and later ancient concept to modern quantum physics. Everything in the universe (no matter how near or far it may be) is potentially connected by the pure motion of the quantum physical fields that form the basis of every material appearance. According to the Greek and ancient idea of how heaven and earth were constructed, this pure motion was to be thought of as a warm breath floating through everything.

Aristotle writes in De Generatione Animalium: "There is something in all seeds that makes them fertile in the first place, namely what is called heat. This is not fire, nor any similar force, but the pneuma embedded in the seed and the sperm, and the nature of this pneuma, which corresponds to the matter of the stars".

The Stoic thinkers derived the concept of pneuma from the medical teachings of antiquity, which were indebted to Aristotle, and developed it into the central principle of their cosmology and psychology (i.e., the doctrine of the soul).

Neume

Already in the early Middle Ages, melodic units, melodic formulas, or melismatic melodic parts were sung over individual vowels-such as the Jubilee, which is sung over the last vowel of the Alleluia. In this case, the term neume was derived from pneuma (gr. πνε어μα pneuma: spirit, breath, air).

At this point, I would like to reiterate that the reason we engage in the study of design history is that we can gain a better understanding of what it means to be a designer today by gaining an overview of the conditions of the time.

In our very brief look at the period before the eighteenth century, that is, before design became a profession in its own right independent of art, we found two basic conditions for those who were entrusted with work close to our contemporary understanding of design, namely the production of illuminated manuscripts, which we would now call editorial design.

To be related to a truth that can only be kept alive by repeating it, that is, by copying the texts and by finding a way to implement a differentiation in them, especially in the aesthetic appearance. Today we call this individual handwriting. No matter how hard one tries to copy as accurately as possible, writing by hand means involuntarily putting one's own movement into it.

To be asked to reach as deeply as possible into one's imagination to find the appropriate images for the figurations of heaven and hell. An imagination or phantasy that is to be understood as a representation of a truth that can only take place in the organs of the individual, between the heart and the brain, where the pneuma itself produces the images of a truth that cannot otherwise be seen with human eyes.

So we have two very close points: The movement of the hand and an imagination of heaven and hell that needs the moving hand to become visible. Both the individual movement and the individual imagination, taken from the fragments of our experiences, are still unconditional for authorship and performance.

The 3rd point

Authorship in the Greek and medieval understanding is first and foremost a surrender to pneuma. In the Middle Ages, pneuma was seen as the divine breath that flows through every element of the universe. Thus authorship, as practiced by Greek and medieval artists and philosophers, was to participate in the breathing of creation in a practical sense-through philosophizing and designing. This presupposes an understanding of a world in which everything is related to God. God was thought of as a personal will, but not as a person. God, according to the earliest descriptions, is to be understood in this sense as JHWH. This series of unpronounceable consonants is derived from the Old Arabic HWH, which means "falling," "blowing," or "loving," as the will that (according to the causative of JHWH, which is HJH) "creates being," "calls into being”.

The third point to be added to what has already been said is the grammatical structure to which one must surrender in order to let the pneuma be materialized by moving according to the neume. In conclusion, here is a summary of our findings:

Movement of the hand or the whole body,

Imagination of figurations based on movements,

Grammatical structure to let the figurations become physically true.

18th Century

The development of communication design is directly related to the ideas of the Age of Enlightenment. The world could no longer be seen as based on circular processes of life, related to the equally circular structure of heaven and hell, but as a chain of causalities.

The meaning of the world before the Enlightenment could only be discovered by tracing the similarities that must be interpreted in order to read the will of God.

Since the Enlightenment, the purpose of the world has been to improve and optimize all naturally given functionalities in order to create the most perfect world possible. Communication design has been committed to this idea since the 18th century.

Pages from 1550 Annotazione on Sacrobosco's De sphaera mundi, showing the Ptolemaic system:

If we understand Communication Design as a discipline that, as its name suggests, is concerned with the design of communicative processes, we can say that the profession began with the Encyclopedia published in France between 1751 and 1772 by Denis Diderot.

The Figurative system of human knowledge from Diderot's Encyclopédie, 1752.

Linné's method for classification of animals, 1735:

The idea is: Everything can be understood and is ultimately reasonable to the extent that we unfold the chains of causality and systematise what we have found according to their progression.

This applies not only to the emerging sciences, but also to the collective and personal shaping of the relationship between the individual and society. It is in this context that Immanuel Kant's definition of enlightenment should be understood:

"The liberation of man from his self-inflicted immaturity.”

Self-inflicted in the sense that every human being is capable of autonomous thought.

Communication design is the concrete form that this takes:

In the practical work of communication design in the 18th century, we find for the first time a systematic description of the what, i.e. the particular object or subject, and a logical argumentation of the why and how.

The task of communication design is not only to illustrate the how, but also to systematise the relationships of the why in the how by summarising all related information in a table.

We still use the same process today when it comes to designing information and information graphics.

Your task:

Choose a physical or media object (or product).

Design the presentation of the product according to the principles found in Didero's Encyclopedia (do in-depth research on this topic):

- Divide the object into its parts.

- Name the parts.

- Show how the object is used in a process.

etc.

In addition, write a brief description of the construction, functionality, and use of the object (or product).

This task is the foundation for the next two tasks in this lecture.

In your research, writing, and creative execution, you will work according to the principles of quality design excellence.

Documentation of the lecture